I was born in Chicago, Illinois, 6 March 1929, to Arthur John and Lillian (O'Keefe) Harris; brought up at Lake Ann, Benzie County, Michigan. Attended one room school houses, until entering Honor Rural Agricultural School where Thelma Swiler and Miss Burke were my favorite and most influential teachers; graduated from Traverse City High School, 1947, where Miss Pagel (of English) and Miss Kennedy, for her direction of Arsenic and Old Lace, were my most influential.

Graduated from

Central Michigan University, 1951, with Bachelor of

Science

Degree, Major Biology, Minors History and English, where Dr. Olive

Hutchinson Krees and Dr. Mary Mathison Wills were most

influential. Ultimately, it was Mrs. Wills who advised me to "get

on the boat" (for England) as soon as possible. High School English

Teacher, Reed City, Michigan, 1951-54. Previously, two ten week summer

sessions of graduate study in English Literature,

University of Colorado, brought my hours in English up to a

major. It also gave me the opportunity to perform in

Twelfth

Night

under the direction of

B. Iden Payne,

B. Iden Payne,

World-Renowned Teacher and Director of Shakespeare

formerly director of The

Memorial Theatre (now "Royal") at Stratford-upon-Avon. Awarded a

Ford Foundation Fellowship for High School Teachers

in 1954 and traveled in Great Britain (where I first went to the

Edinburgh Festival, at which I saw a great exhibition of the works

of Diaghilev. I first traveled through Scotland (as far as the

Outer Hebrides), and down through the Lake District, York, the Bronte

Country, etc., all the while visiting schools, studying their drama

programs. Late in 1954, I began studying at The Shakespeare

Institute, University of Birmingham, at Stratford, 1954-56, under the

direction of Professor Allardyce Nicoll.

I completed my M.A. thesis there under the direction of

R. H. Hill

on a stage history of

Measure

for

Measure 1959.

Returned

to America, 1956, to teach at Arthur Hill High School,

Saginaw, Michigan, 1956-59. While there, I produced the first act of

Hamlet

as an experiment (later presented before the entire student body)

and later mounted a full-scale production of

Twelfth

Night

for the public with important assistance in costumes and

sets from Constance Bassil. From 1959 to 61, I was Instructor in

English at Central Michigan University. In 1961, I returned

to the Institute at Stratford to begin work on the Ph.D., this time

focusing on the dissertation,

"King

Lear in the Theatre: A

Study of the play Through the Performances

of Garrick, Kean, Macready, Irving,

Gielgud, and Scofield" under the direction of

John Russell Brown:

Ph.D. granted in 1966.

Those first two study periods ('54-'56 and '61-'63) at Stratford were

perhaps the most influential of my life, not only because I was a

graduate student among such important scholars in a small and very

historic setting, but also because I was able to experience world

famous theatre

Laurence Olivier's

Laurence Olivier

as Macbeth 1955

photo by Angus Mcbean

Macbeth,

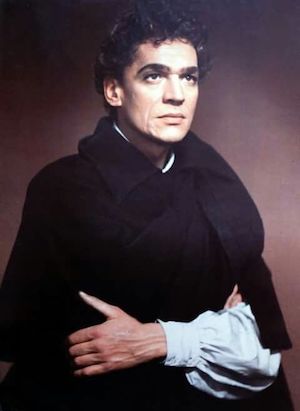

Paul Scofield's

Paul Scofield As Hamlet in 1955

Hamlet,

John Gielgud's

John Gielgud As King Lear in 1955

King

Lear and

Much Ado (with Peggy

Ashcroft) to mention only a very few. In England at that time you

had closer contact with the actors and I later spent one year living in

a thatched cottage on the Village Green, Luddington outside Stratford

in the "digs" where Scofield had lived as he rose to fame. One was

always in the presence of great actors: Edith Evans often had

lunch at Hall's Croft, Shakespeare's daughter's home, with students

in the club room of the house. I think, too, that perhaps I am

the only person in the world who saw Olivier's

Macbeth

13 times over a long season and my hair stood on my arms

every time I saw it. His performance of

Titus Andronicus

Laurence Olivier As Titus Andronicus in 1955

in Peter Brooks'

production was also indelibly planted in my memory.

In 1963, I took a position as Instructor of English at The University of Michigan, later Assistant Professor, until 1967, when I settled at Eastern Michigan University, for the remainder of my academic career, teaching both undergraduate and graduate courses in Shakespeare, as well as graduate Whitman and Dickinson, retiring as Full Professor at 65 in 1994. I took students several times to productions at Stratford, Ontario. In 1974, '76, and '78, I led students to The Shakespeare Institute for a spring course in "Shakespeare and the Shakespeare Country." In 1988, I also participated in an exchange program with Nonnington College in Kent, Fall Semester, 1984.

Publications include

"William Poel's Elizabethan Stage: The First Experiment,"

Theatre

Notebook,

Summer, 1963, inwhich I revealed the full description of Poel's famous

Elizabethan stage for the first time;

"Garrick, Colman, and

King

Lear:

A reconsideration,"

Shakespeare

Quarterly, Winter,1971,

in which I proved that, contrary to popular belief, Garrick was

not the foremost restorer of Shakespeare's text to the stage after the

alterations of Naham Tate. Instead, it was George Colman, his

contemporary man of the theatre. (This does not diminish

Garrick's genius

as an actor or his status as probably the greatest promoter of

Shakespeare in the

theatre.) This essay has been more recently republished in

volume 9 of Steven Orgel's reprints of classic essays of the 20th

century;

"William Poel's Measure

for Measure

at Stratford-upon-Avon,1908,"

Speech

and

Drama,

vol. 37, no. 1,1988, in which I develop a full-length study

of one of Poel's most significant productions;

"Ophelia's 'Nothing': "It Is the False Steward that Stole His

Master's Daughter,"

Hamlet

Studies,

1997, in which I present a strong argument for my theory that King Claudius

abused and later destroyed Ophelia. The evidence is particularly

revealed in the crux line she herself speaks to her brother (IV.v.):

"It is the false steward that stole the master's daughter." Reverse the

line and you get: "It the false master [Claudius] that stole the

steward's [Polonius] daughter." Laertes' own following line reveals the

importance of it: "This nothing's more than matter," and, at the outset

of the scene, in her madness she is said to speak

"half-sense", but there is also significant evidence throughout the

play. Remember,

Hamlet

is a play about characters who are suspicious, uncertain. So too

should be the audience; we may never know for certain the truth of my

theory, but we should be at least highly suspicious about what happens

to Ophelia.

Most recently, in a note in

The

Explicator

(Winter 2004), Frankie Rubinstein and I collaborate to prove that the

crux line in

The

Merchant

of

Venice,

"And if on earth hedoe not meane it, it/Is reason he should

never come to heaven" (3.5.8.) should follow the three early

texts and stick to Shakespeare's "mean", not Alexander Pope's

changing of "mean" to "merit", as do the

majority of modern editions, the problem being that editors

have often missed the bawdy in the scene and they often seem not

to know that the first definition of

'meane' in the Middle English Dictionary is "sexual intercourse."

Another essay by us

on Jessica and her importance to the play at large appeared

in December 2004 in

English

Language

Notes.

It will help readers to see her role more clearly and encourage

directors not to cut this small but important scene from their productions.

Research Presentations include:

"Who Killed Ophelia?", the annual meeting

of the Michigan Academy, Central Michigan University, March, 1977;

"'A

Tricksy Word': The Meaning of Jessica's 'Meane'," The Poetry, Drama,

and Prose of the Renaissance and Middle Ages, at The Citadel,

Charleston,

South Carolina, 1991;

"Hearing Ophelia: 'It is the false steward that stole his master's daughter'" at a Renaissance dinner before the Book Club of Detroit, The Scarab Club, Detroit, Michigan, December 7, 1999.

Particularly since 1974, I have coupled this literary and academic career with devotion and commitment to historic preservation in the community of Ypsilanti, Michigan.