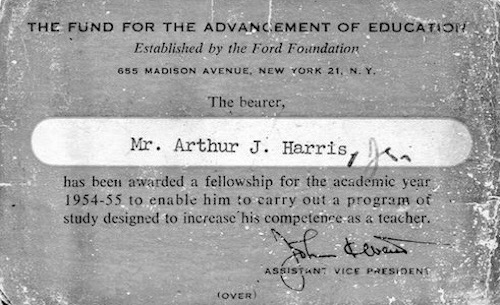

Was I lucky? Ford had given me the opportunity of a lifetime.

As luck would have it, I found I was living so economically

(approximately, $8.56 per week, room and board) I could stay on for a second year and begin

my Master of Arts degree. This would be in 1955-56.

John Russell Brown,

who had earlier been most helpful, came to my rescue and suggested I do a stage

history of one of Shakespeare's plays as performed at the Memorial Theatre.

This idea fit perfectly with the original plan with Ford: to enhance my interest in theatre.

I wanted to do Big Things, so I suggested I study King Lear,

a play I had read in undergraduate school under Dr. Mary Wills. Dr. Brown wisely steered me

clear of such a monumental task and instead recommended Measure for Measure.

I hardly knew the play. After a reading or two, I saw his point, the play itself interested me,

and I wrote up a proposal. There had been only four directors who had produced the play at Stratford:

William Poel (1908)

William-Poel,

World-Renowned Actor and Director of Shakespeare

W. Bridges Adams (1924 and 1931), Frank McMullen (an American, in 1946), and Peter Brook (1950),

who had a very long and enormously successful season only four years before I first arrived in England

in August 1954, though I had no idea of the fame of the first and last person on that list: Poel and

Brook. I had, however, attended

two ten week summer sessions at The University of Colorado, at Boulder, where one summer

B. Iden Payne

B. Iden Payne,

World-Renowned Teacher and Director of Shakespeare

directed Shakespeare's Twelfth Night and I got two small parts, the Sea Captain and the

Priest, in the production—and Payne had worked with Poel!

(Read about B. Iden Payne on Wikipedia.)

I immediately set to work collecting data for such a task. At that time, the Theatre Library

was in the part of the theatre that had survived the Great Fire that had burned out the old

(and very Victorian) building. It had by this time become the back and west side of the new

art deco theatre, designed by an American woman, in the thirties. The reading room of the library

was quite small with only a few chairs and fewer tables, and Miss Eileen Robinson, as Librarian,

kept it immaculately in order, while the holdings were kept protected in an area behind.

To me the most important holdings were the original prompt books, because they held each

director's cuttings, movements, much of the entire plan of the production. And of course she

had on hand photographs of everything. It was right there, not more than eight minutes walk

from the Institute.

Actually, it was the second year at Stratford that became the biggest boon to me, the year that

the Ford Foundation could feel proudest to be responsible for. I was so lucky.

The most notable other person who spent time there was

Tanya Moiseiwitsch, the famous stage designer who was primarily responsible for the

platform stage at Stratford, Ontario, and went from there with Tyrone Guthrie to Minneapolis

to help design the great new theatre there. We had lots of conversations together, at least

when other visitors were not around. Ms. Moisiavitch was not at all a pretentious or distant

person; she was, rather, very natural to talk with. However, Miss Robinson told us how disconcerting

it was when Americans would open the door—just to look and say loudly (out of the blue) "Hi!"

She wasn't used to such familiarity with strangers in Britain; and she never quiet knew how to respond.

But it was altogether a perfect place to work on my subject: a first class collection of manuscript

material almost at my fingertips, an efficient yet warm and helpful woman who knew her collection,

a small comfortable library room, and a friendly woman who would go on to become world famous

for her contribution to the Elizabethan stage in North America.

One day Miss Robinson brought out of storage a sale description catalogue of William Poel's

famous "platform stage" built by him in the late nineteenth century to replicate, as best he could,

what the Elizabethan stage would have looked like. To my amazement, this must have been the only

copy extant, because

Robert Speaight

Robert Speaight, 1904 – 1976

Actor and Writer of theatre and biography

never mentions it in his full length biography of Poel or other

writings, nor had any of the multitude of other writers who had over the years commented on Poel.

In time, I wrote it up and had it published (with photographs) in

Theatre Notebook,

(XVII, #4, Summer 1963) a small but significant journal published in London.

Another article of mine, probably the most detailed and thorough description of Poel's production of

Measure, as it was performed at Stratford-upon-Avon in 1908, was much later published in

Speech and Drama, (Vol. 37, No. 1, Spring 1988).

This production was seen by the then young Sir Barry Jackson, of Birmingham, who would go on to open

a theatre in London and later at Stratford and Malvern, as well as his own Birmingham Repertory Theatre,

to influence English theatre and discover an amazing number of great English actors, called Poel's

1908 Stratford production for him the supreme "awakening experience." The Speech and

Drama essay recreates everything about that production as a great moment in the history of

the twentieth century English theatre, right down to the weather.

Of course, I frequently had to go to the Shakespeare Library in Birmingham, and other libraries,

especially the Bodlein at Oxford, the British Museum in London, along with the Enthoven Collection

at the Victoria and Albert Museum, etc., but the bulk of the work could be gleaned right at Stratford.

I also took courses at Birmingham at the University to make up for deficiencies in background,

including one I remember, a class from the unique and eminent scholar, I. A. Shapiro, who just

recently died in 2004 at the age of 99. One day I had not finished a reading before arriving at the

university and his challenge to me was delivered in his usual very pointed question: "And what were

you doing on the train (from Stratford)? Counting the rabbits? There, of course, had to be photographs

for both my Master's Degree and, later the Ph.D., but the theatre library at Stratford had a most

complete collection of these, thanks mainly to Miss Robinson. I also traveled to the vast newspaper

collection at the

Collindale Library at Golder's Green,

Collindale Library at Golder's Green

Important Research Source for Jack Harris' MA and Ph.D. Thesis

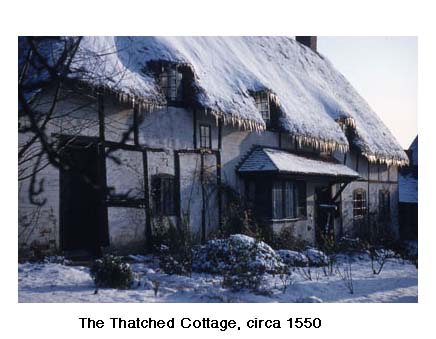

outside London; but I still lived at the Thatched Cottage most of the time. I had found a very

old bicycle in the garage behind the Institute and traveled by that means between the Institute

and "home." That, in fact, was when I really heard my first performance of the English lark,

made so famous by Shelley's poem, "To a Shylark," rising from a field beside the road and into

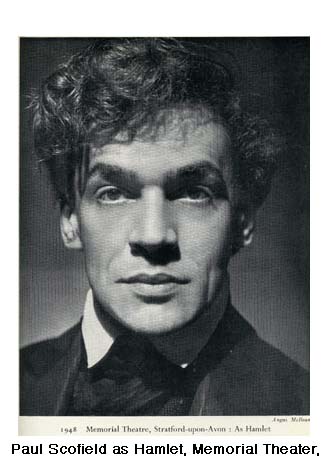

the sky to do his magical firebird dance. The other special treat I remember was that Paul Scofield

came back one day to visit Mrs. Headland and served her three tenants breakfast the next morning.

It was like having Gary Cooper do the same for you here in America.

Thus that second year was primarily devoted to data collection.

As I recall, only a small portion of the actual writing was done that second year;

the rest would be done after my return home to Michigan. Most of the writing took place

in a vacant house belonging to my parents, and John Russell Brown edited whatever I sent

him by post wherever he was. For example, I still have at least one note here from him

in Washington, D.C. His help was invaluable. What my work reveals, quite clearly, is

that each director brings his own reading to the play and cuts whatever he feels is either

unnecessary, or too shocking for his audience, or whatever simply doesn't support his own

particular vision for the work. In every case, I found that all four directors were limited

in their vision of Shakespeare's own plan. One needs to say about each production that it is,

say, "Shakespeare's and William Poel's Measure for Measure or "Shakespeare's

and Peter Brook's Measure for Measure," etc. In fact, it is said that

Brook, in a six hour production of Hamlet he produced for his family at Christmas when

he was seven, referred to it as "P. Brook's and W. Shakespeare's Hamlet."

He has carried this philosophy pretty much with him throughout his long and famous life.

He is brilliant. He is a genius. I know, because I have seen his Paul Scofield "Moscow"

Hamlet and his Scofield on the stage in other work. But in his Shakespeare he cut the text

to make Shakespeare's play his own; and this, I believe, is where he falters.

The Measure for Measure work was completed in Michigan, where I taught at

Arthur Hill High School for three years and was then invited to teach at the university level at

Central Michigan University. I then returned to Stratford-on-Avon for two more years of study

(1962-64), working at University of Birmingham and Stratford, when I began work on my first love,

King Lear. This work followed the plan for the M.A., another

stage history and interpretation, but with a major difference: This would be a study, not just of a

play at one famous theatre, but a study that would begin with an overview of an early alteration of

Lear, the King Lear of Naham Tate, 1681, a radical alteration of Shakespeare's

original that held the stage, wholly or in part, into the nineteenth century and trace the play

through three centuries of theatre performance: David Garrick, Edmund Kean, William Charles Macready,

Henry Irving, John Gielgud, and Paul Scofield as King Lear.

The famous Peter Brook-Scofield Lear came at the end of this second residence at Stratford

and its significance was such that I had to incorporate it into the original plan. Again, as in

the M.A. thesis, in my final chapter of the book I summarize what each director missed or deleted

or deliberately altered to suit his own plan for the drama. Anyone who thinks there is ever a

"complete text" of a Shakespeare play in performance is badly misinformed, in my opinion.

I have never seen a prompt book that did not cut something or other, and in most cases, a

lot of the text.

On three different occasions in the seventies, I took groups of students from America to

Stratford-upon-Avon and the Shakespeare Institute to study in a spring course and experience

something of what I had there. We studied at the Institute, heard lectures from professors,

talks from well-known actors and critics, traveled to great houses and gardens. It was a complete

cultural experience. I had also become involved in historic preservation, as Vice-chair of the

Historic District Commission, and President of the Ypsilanti Heritage Foundation (not the conservative

group in Washington) as well as editor of

Heritage Foundation's newsletter.

We made an enormous difference.

Happily, Shakespeare, in my opinion, still awaits a full performance, not so much in terms of

keeping every word of the text in the performance, but in keeping what is clearly Shakespeare's

intentions foremost in any production. That is why I, more than fifty years after receiving a

Ford Fellowship, thank Ford profusely for changing my life and the lives of those around me, first,

for the M.A. thesis, the above Measure for Measure, a Stage History and an

Interpretation," and, second, a similar, but larger, volume, " on "King Lear". in the Theatre:

A Study of the Play Through the Performances of Garrick, Kean, Macready, Irving, Gielgud,

and Scofield. Both of these works were done for the University of Birmingham, the first

completed in 1959 (213 pp.) and the second in 1966 (458 pp.). In both cases, I look at these

works now as even more important than they were back then, particularly the Lear,

for it involves a better known and a greater play, as well as three centuries of great actors,

culminating with Gielgud, whom the world has recently lost, and Scofield, who is now 83.

Recently there has been a theatrical biography of Gielgud (Sheridan Morley's John Gielgud, 2002),

which essentially ignores cuttings of the text. Moreover, I more firmly now believe the world

has yet to see the real Shakespeare's King Lear.

My belief is that when Shakespeare sat down to write King Lear he asked himself not so much, "What story do I want to tell?" but rather "What is the challenge I can give myself and my audience?": "What powerful impact do I want my audience to feel?" And, at least in Lear, Shakespeare's answer seems clear to me: he wanted to take on the challenge of the most difficult human subject possible: an ancient king so old ("four score and upwards") few could identify with him, a man so stubborn that hardly anyone could feel for him. With this as starters, Shakespeare was then determined to create the closest, most powerful identity connection between his actors and his audience imaginable. The simple story would lead his audience, first to fear for Lear in his error in judgement but also the audience to fear for themselves, for this fear is universal: we all live with the fear of not knowing enough to avoid catastrophe.

The idea is basic to all of us: It is at least as old as Greek drama. Shakespeare wanted to arouse this fear, first, and then awake such pity for those who are shut out of their "safe" environments, that the audience becomes involved in taking sides between the essentially bad, self-centered, possessive characters (e.g., Edmund, Goneril, Regan Cornwall, et. al.) and the considerate and giving characters (Kent, Cordelia, Gloucester, Fool, Albany, and all those in the shadows, including the servants left after the blinding of Gloucester, who seek to ease his pain). It hardly matters that Lear dies, for at the end he comes to us, with the dead Cordelia in his arms, asking us to "Howl, . . .", and he SHOWS us directly: "Do you see this?" He confronts us with lost love, and we identify, for it is our loss too. And it is perhaps the worst loss, a child, a favorite child. Between fear and pity, aroused out of the actions on the stage, there would arise such an emotional involvement that it would not be easy to recover or forget. This was Shakespeare's intention. It happened, I remember reading somewhere, to Joshua Reynolds when he saw Garrick do Lear and it happened to me when I saw Gielgud do the same role. Like Reynolds, I could not look at the text of Lear without sharp reaction. After the performance, I was taken backstage to Guilgud's dressing room door; I told him how affected I was. His simple answer was typical of him: "Sometimes I know what I'm doing, and sometimes I don't." Garrick was doing a largely Tate text, in which Cordelia does not die, but Lear's suffering alone carried him along; I was listening, in Gielgud, to a largely Shakespeare text. Tate's text, painful as it is to us but powerful to Reynolds, made its point; Gielgud's Shakespeare text made its point to me. Shakespeare's intentions, the essentials of fear and pity, in a universal human experience, held fast.

Gielgud had been mislead by developments around him and he attempted to remove sympathy and pity from this 1955 Lear. Toward the end of this new Lear, he 'failed' and returned to his earlier more sympathetic Lears and this was enough to move me forcibly. I believe I prove that, particularly in the cases of Gielgud's 1950 Lear and the debacle of his production of the 1955 Noguchi King Lear, he was determined not to be seen as living in the past and was influenced by new movements, such as Polish critic Jan Kott, the Irish playwright Samuel Beckett, and the British director Peter Brook: all of these men were moving toward a new view of life that would be reflected in their works. Certainly in Brook's efforts to remove sympathy altogether in the 1962 Paul Scofield Lear, he succeeded in defeating, or nearly defeating, Shakespeare's original intentions: Shakespeare wanted complete identification between actor and audience; whereas they wanted distance between actors and audience. Look on mercilessly and the impact would be more powerful, they all seemed to say. They saw the universe and human experience within it as meaningless; Shakespeare wanted to create meaning and involvement. They wanted coldness, emptiness; he wanted warmth, human warmth, and love. Gielgud AND Scofield, as individuals, if left to their own devices, could have given them the latter, but were influenced or downright directed away from such feelings. My point is that we have to return to the text, and Shakespeare's efforts to engage us more fully. We must allow Shakespeare's clear purpose to evoke, at first, fear, and soon emotional identity with those who are cast out: Cordelia, Kent, Edgar, Lear, and Gloucester. And the Fool follows. That is why I say it is not too late to publish the larger writings that I have kept unpublished until now. Whenever the director thinks that his Lear is more important than Shakespeare's, as far as I'm concerned, he limits, drastically, the full impact of the play.

"At the latest minute of the hour," I hope that you will accept my belated thanks for that Fellowship, given so many years ago. I have, between those early stages of my career and now, published in Shakespeare Quarterly, Hamlet Studies, Speech and Drama, Theatre Notebook, and most recently The Explicator and English Language Notes (both jointly with Frankie Rubinstein in 2004). Now I want to get into print these two larger works that I believe are ripe for publication. I am now 76, retired ten years, and still working on what your fellowship got me onto: I don't want to leave these larger (and I think quite readable) works go unpublished.

In any case, thank you again Ford Foundation, for what you did for me in 1954! The sum was minimal then (I believe something like $8,000!) but it made such an enormous difference to me and the world. You never asked for this long letter, or any report to my knowledge, but I hope you can see that I made good use of your largess. At the same time I can tell you that one of the stipulations of the award was that I return for at least one year to the high school that I left; but back then I of course wrote Godfrey T. Norman, Superintendent, and he wrote back and urged me on. But this last summer, I got a phone call out of the blue from a leader of the class that graduated from Reed City High School the year I left. He was ecstatic that he had at last found me alive. We were invited to a weekend celebration of their 50th reunion of that class, visited the old high school (about to be torn down), banqueted all weekend, and had a glorious time. They taught me and I taught them, as of yore. It was the surprise of a lifetime, so I did, in fact, finally "go back."

Yours sincerely,

Dr. Arthur J. Harris, Professor Emeritus,

Eastern Michigan University,

Ypsilanti, Michigan 48197

and "got on the boat" as soon as possible and headed for England on a Dutch liner

with a whole lot of other students.

and "got on the boat" as soon as possible and headed for England on a Dutch liner

with a whole lot of other students.